How Feudal Lords and Dynasties Hollowed Out Pakistan’s Politics

By Aman Abdullah Shahid -

If Pakistan’s first decade established the dominance of unelected institutions, the decades that followed revealed another tragedy: those who claimed to represent the people often served only themselves.

While the military and bureaucracy provided the architecture of control, it was Pakistan’s civilian elites - feudal landlords, dynastic families, and corrupt politicians - who ensured that democracy remained hollow.

The result was a political order where elections took place, parliaments convened, and constitutions were written - but the principles of accountability, equality, and representation remained distant dreams.

The Feudal Order That Never Ended

At independence, Pakistan inherited not only the institutions of the British Raj but also its agrarian hierarchy.

In provinces like Punjab and Sindh, colonial authorities had relied on landed magnates to collect revenue and maintain loyalty. These landlords were rewarded with vast estates and political influence.

After 1947, they became the backbone of Pakistan’s new political class. Many early Muslim League leaders were themselves members of the landed elite, more concerned with preserving their social dominance than building participatory institutions.

Unlike India, which undertook serious - if uneven - land reforms, Pakistan’s rulers never dismantled this feudal structure. The countryside remained locked in systems of dependency, where tenants and peasants owed allegiance to landlords who controlled access to credit, water, and even local justice. In these conditions, political consciousness was blunted by economic fear.

Land reform became one of Pakistan’s most enduring political slogans - and one of its greatest deceptions.

Successive regimes promised redistribution, yet every attempt was neutralised by the same landed interests it was meant to challenge.

- Ayub Khan’s reforms (1959): Presented as part of his “modernising” project, they set generous ceilings that allowed large landowners to keep their holdings through benami (proxy) ownership. Implementation was weak, and the same families continued to dominate rural politics.

- Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s reforms (1972 & 1977): His populist rhetoric inspired hope for change, but enforcement was again selective. Many of Bhutto’s allies were themselves landlords who quietly subverted the process.

- Zia-ul-Haq’s regime (1977–88): Rolled back what little progress Bhutto had made, restoring privileges to the landed class in exchange for political support during his authoritarian rule.

Each reform cycle ended where it began: with the rich retaining their land and the poor retaining their servitude.

Feudalism as Political Culture

Feudalism in Pakistan is not merely an economic system - it is a social and political mindset. Landlords do not just own property; they own influence. They mediate disputes, decide votes, and command loyalty. For the rural poor, dependence on these patrons shapes daily life, leaving little room for dissent.

As one scholar observed, feudalism functions like a narcotic: it dulls class consciousness, discourages collective mobilisation, and replaces citizenship with clientship. Political allegiance becomes personal rather than ideological - a relationship of obedience, not rights. This dependency has stunted the development of democratic accountability. When political survival depends on pleasing a landlord rather than participating in fair governance, democracy becomes little more than a performance.

The Dynastic Turn

If the countryside was captured by landlords, the cities were soon dominated by dynasties.

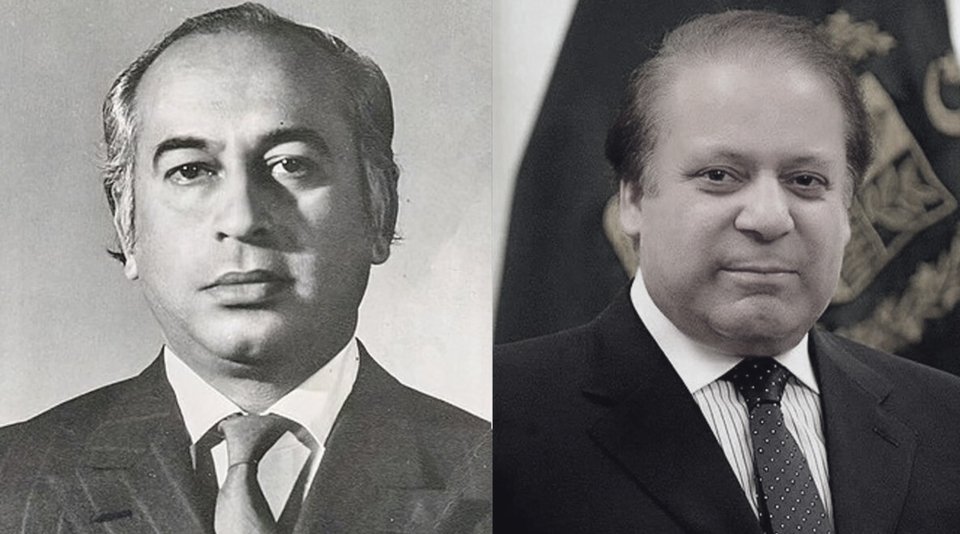

By the late 1960s, two political families - the Bhuttos and the Sharifs - had emerged as Pakistan’s most powerful civilian actors. Their parties, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League (PML), became vehicles not for ideology but for inheritance.

- The PPP, founded by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1967, blended populism with patronage. After Bhutto’s execution by General Zia in 1979, leadership passed to his daughter, Benazir Bhutto, and later to her husband Asif Ali Zardari and their son Bilawal.

- The PML, reinvented multiple times, became synonymous with the Sharif family. Nawaz Sharif, a businessman from Lahore, rose to prominence under Zia’s patronage and built a political dynasty encompassing his brothers, daughters, and nephews.

Both parties adopted the rhetoric of democracy but practiced dynasticism. Loyalty flowed upward to families, not institutions. Merit and internal debate were sacrificed to lineage and loyalty.

The Weaponisation of Law

In a functioning democracy, law serves as a neutral arbiter; in Pakistan, it became an instrument of political warfare. Both the PPP and PML have, at various times, used the National Accountability Bureau (NAB), Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), and judiciary to target rivals.

When Nawaz Sharif was in power, corruption charges rained down on PPP leaders. When Benazir Bhutto returned, she repaid the favour. Accountability became a farce - a mechanism of revenge rather than reform.

This cycle eroded public trust in the justice system. The law came to symbolise not impartiality, but persecution. Even the judiciary, meant to uphold constitutionalism, frequently sided with whichever faction aligned with the establishment. From disqualifying prime ministers to legitimising coups, the courts played a crucial role in sustaining the illusion of legality while undermining its substance.

Corruption in Pakistan is not a side effect of politics - it is its central organising principle.

Public office grants access to patronage networks: contracts, loans, and subsidies distributed to loyalists who then fund the next campaign. This circular exchange of favour and finance ensures that political power remains concentrated among the few. A vivid example is the sugar industry, dominated by politically connected families. Through price manipulation and control of distribution, these elites extract massive rents while driving up costs for consumers. The same families use their profits to consolidate political influence - turning governance into a self-sustaining racket.

The Rivalry That Broke Democracy

Following General Zia’s death in 1988, Pakistan returned to civilian rule. It should have been a moment of democratic renewal. Instead, it became a theatre of vendetta. For over a decade, the PPP and PML alternated in power, each accusing the other of corruption, each conspiring with the establishment to bring the other down.

Between 1988 and 1999, four elected governments were dismissed on charges of incompetence or graft. Rather than uniting to defend democratic norms, both parties treated the military as a referee - inviting it to intervene when convenient, then condemning it when not.

This constant infighting allowed unelected institutions to retain control behind the scenes. By the time General Pervez Musharraf seized power in 1999, Pakistan’s politicians had already done much of the work for him. Throughout this period, the judiciary remained an unreliable guardian of democracy. While it occasionally resisted executive overreach, it more often lent legitimacy to it.

The disqualification of Nawaz Sharif in 2017 over the Panama Papers - a ruling many saw as influenced by establishment pressure - echoed a long tradition of selective justice. Pakistan’s courts have consistently applied accountability with bias, targeting those out of favour while shielding those in alignment with power. This pattern has not only eroded faith in the judiciary but also reinforced the military’s role as the final arbiter of politics.

By the early 2000s, Pakistan had perfected a form of performative democracy - one where institutions exist, but purpose does not. Political parties hold rallies and elections, but real decision-making remains confined to family drawing rooms and military headquarters. Parliament is convened, but rarely empowered. The public votes, yet policies serve private interests.

This is not democracy in crisis - it is democracy by design, engineered to preserve elite dominance. For most Pakistanis, politics remains distant from daily life, an arena of corruption and conspiracy rather than empowerment. The persistence of poverty, inequality, and institutional weakness is not accidental; it is the logical consequence of a system that rewards loyalty over merit and inheritance over accountability.

Democracy Without Democrats

Pakistan’s tragedy is not that it lacks democratic procedures - it is that it lacks democratic actors. The PPP and PML, despite their rhetoric, have failed to nurture a generation of leaders committed to reform. Their preoccupation with patronage and protection has left the political landscape barren of principle.

In this vacuum, the military has repeatedly stepped in, presenting itself as a stabilising force against civilian dysfunction. Yet the cycle only perpetuates itself: weak politicians justify intervention, and intervention ensures politicians remain weak.

Pakistan, in effect, has built a democracy without democrats - a political system that mimics representation while entrenching hierarchy.

Next in the Series: “From Ballots to Barracks”

The final part examines the military’s entrenchment in politics and the rise and fall of Imran Khan - a reformist who claimed to challenge the establishment and became the latest casualty of Pakistan’s unbroken cycle of elite power.

Member discussion