The Political Entrenchment of the Military - and the Rise and Fall of Imran Khan

By Aman Abdullah Shahid -

If dynastic rivalry prevented true parliamentary democracy in Pakistan, and feudalism entrenched oligarchic politics, it was the military that ultimately cemented itself as Pakistan’s most powerful and enduring institution. Since 1958, the army has staged three successful coups, multiple ‘soft’ interventions, and has maintained influence even during periods of civilian rule.

Unlike political parties, which can rise and fall, or dynastic leaders who depend on electoral cycles, the military has remained a permanent feature of Pakistan’s political landscape – the ultimate arbiter of the state. And thus, the narrative of Pakistan’s political development is inseparable from the recurring interventions of the armed forces.

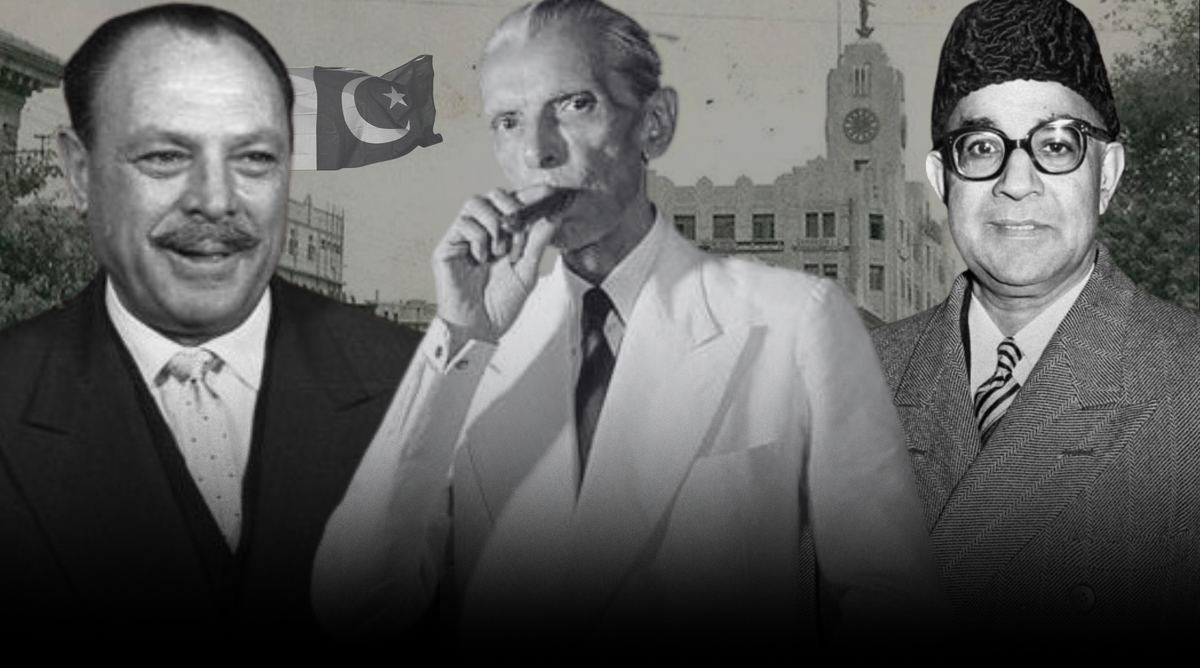

Pakistan's 3 Major Military Coups

Pakistan's first major military coup occurred in 1958 after the repeal of its first constitution. President Iskander Mirza used the military, led by General Ayub Khan, to suspend parliamentary democracy under the pretence of political instability and the failure of civilian politicians.

However, within weeks Mirza was ousted by Ayub, who installed himself as the country’s first military leader. In 1962 he introduced a new constitution, which replaced parliamentary democracy with a presidential system and concentrated power in his own hands.

Ultimately his authoritarian leadership style generated political alienation and fuelled nationalist sentiment. War with India in 1965 further discredited his rule and led his eventual resignation in 1969.

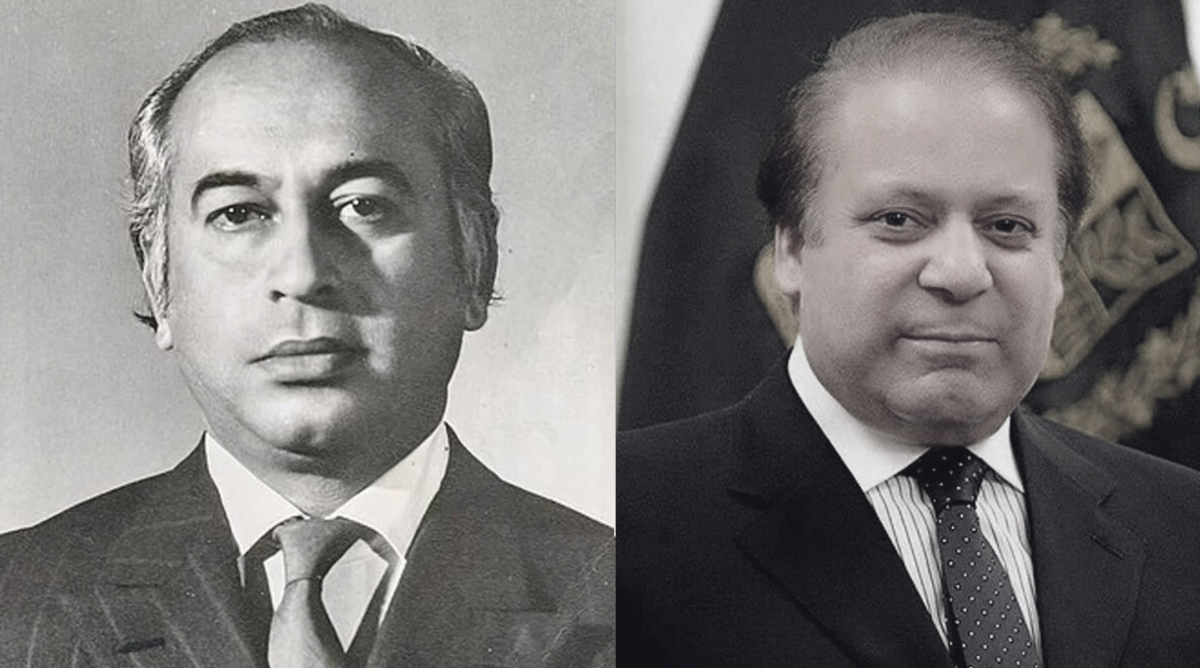

The second decisive militant intervention came in 1977, when General Zia-ul-Haq overthrew Zulfikar Ali Bhutto following widespread protests against alleged electoral rigging. General Zia initially promised to hold elections within 90 days but instead imposed an 11-year dictatorship, under which the country experienced a fusion of authoritarianism with Islamisation.

He introduced Hudood ordinances, blasphemy laws, and a range of Islamic injunctions, embedding religion into Pakistan’s legal and political order. As a result of his partnership with the U.S. during the Afghan jihad in the 1980s, he received billions of dollars in financial aid, all of which was channelled through the army, empowering the military institutionally and economically.

The third major military coup came in October 1999, when General Pervez Musharraf seized power after Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif attempted to dismiss him. His coup was justified on the grounds of civilian incompetence, corruption, and political instability, with Musharraf presenting himself as a reformer advocating for “enlightened moderation”.

His coup coincided with the post-9/11 era, which dramatically increased Pakistan’s geopolitical standing. As a frontline ally in the Global War on Terror, Pakistan received billions in military and economic aid, much of it (again, as under Zia-ul-Haq) funnelled through the armed forces.

However, Musharraf’s experiment with controlled democracy eventually flatlined by the mid-2000s. His dismissal of Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry in 2007 triggered a mass lawyers’ movement and by 2008, amid mounting protests, Musharraf resigned.

Military Influence Beyond Coups

The military’s influence in Pakistan has extended far beyond periods of direct military rule. Even under civilian governments, the army retained decisive control over national security, foreign policy, and significant aspects of the economy. Civilian leaders that have challenged this control faced removal, imprisonment, or exile.

The concept of “hybrid regimes” aptly captures this phenomenon. Civilian leaders are ‘allowed’ to govern, but only within the limits set by the military. Policy autonomy is curtailed, dissenting politicians are neutralised, and the judiciary and media are often co-opted to legitimise the preferences of the establishment.

The judiciary has been consistently complicit in legitimising military interventions, repeatedly invoking doctrines of necessity, expedience, or national interest to sanction authoritarianism. Even in recent years the judiciary has been accused of selective activism – aggressively persuing cases against certain politicians whilst avoiding scrutinising certain military figures.

Further still, the military has been able to secure de facto control via its major economic programs, establishing Pakistan’s own “military-industrial complex”. Through foundations like the Fauji Foundation, Army Welfare Trust, and Bahria Foundation, the military has been able to control vast business empires spanning real estate, agriculture, manufacturing, and services.

Thus, by the 21st century, it has become clear that the military is not merely an arbiter of politics, but its most enduring participant. Civilian governments have functioned, at best, as junior partners in a system dominated by khaki. This dynamic explains why Pakistan’s democracy remains perpetually fragile, why no prime minister has completed a full term, and why political leaders like Imran Khan are silenced the moment they attempt to assert independence.

Imran Khan – a New Hope?

Imran Khan's political career has stood out as a beacon of hope for civilian governance in Pakistan. Unlike the dynastic elites (who inherit their positions) that have traditionally made-up Pakistan's political sphere, Khan entered politics as an outsider. His rise was grounded not in patronage networks but genuine public support and for millions of Pakistanis, particularly the young and disillusioned.

After captaining Pakistan’s cricket team to World Cup victory in 1992 and founding the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital, and later Namal University, Khan turned his head to politics, founding the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) in 1996. He promised politics of justice, accountability, and dignity, free from elitist exploitation and feudalism – a “Naya Pakistan” (New Pakistan).

By 2018 Khan had won the premiership with a popular mandate. His government introduced ambitious reforms aimed at improving social welfare, better access to healthcare, and improving education, as well as ending Pakistan’s dependency on foreign aid.

Yet Khan’s determination to govern independently inevitably brought him into conflict with the establishment. His insistence on asserting civilian authority in areas traditionally monopolised by the establishment – appointments within the security services, foreign policy decisions, and economic policy direction – broke the unwritten code.

By early 2022, the establishment had determined that Khan was no longer manageable. His removal via a parliamentary no-confidence vote – technically a constitutional process, but one widely seen as engineered by elite coordination – revealed the limits of civilian autonomy.

Khan’s arrest and avalanche of legal cases put against him fit a familiar pattern in Pakistan’s history, where leaders who confront entrenched authority are criminalised, delegitimised, and silenced. The script has been repeated: no civilian leader is permitted to survive a confrontation with the establishment. Khan, despite his popularity, had become the latest victim of this cycle.

Pakistan’s economic standstill

As a result of elite capture, Pakistan’s economy has been locked in a cycle of dependency. Fiscal deficits, external debt, and balance-of-payments crises recur with alarming frequency, forcing the country into repeated IMF programmes. Since 1958 Pakistan has entered IMF arrangements more than 20 times – among the highest in the world. Each programme provides temporary relief but fails to address the structural causes of economic crisis, since the very elites responsible for mismanagement remain in power.

Against this backdrop Imran Khan had represented an alternative. His government inherited a crisis-ridden economy in 2018, yet his vision emphasised self-reliance, accountability, and redistribution. He framed his agenda around the ideal of a welfare state modelled on the Riyasat-e-Mediana (State of Medina), where rulers were accountable and citizens were protected.

In the end, it was precisely because Khan’s agenda threatened entrenched privileges that the establishment and the military closed ranks against him. His ousting in 2022 was not merely a political manoeuvre, but an elite counter-offensive designed to restore the old order of corruption, patronage, and dependency.

From Ballots to Barracks

The history of Pakistan is a history of interrupted mandates, aborted reforms, and a democracy held hostage by entrenched elites. The country has never been allowed to cultivate the institutional stability that is the bedrock of genuine democracy. Each moment of promise has been smothered by the same configuration of power: a nexus of feudal landlords, dynastic politicians, and an omnipresent military establishment.

The consequences of elite capture are not confined to politics – they are etched into Pakistan’s economic stagnation, its cycles of dependency, and its inability to provide basic dignity to its citizens. Each IMF bailout, each episode of inflation, each closure of a factory or collapse of a public service is not the result of bad luck but of deliberate misrule by those who monopolise power.

Pakistan today stands at a crossroads. It can either continue in this cycle or it can confront the establishment that has strangled the rule of law for 77 years. The stakes could not be higher, but legitimacy cannot be imposed upon the people of Pakistan.

In the end, Pakistan’s story will be decided not by its elites, but by whether its people can finally reclaim their state from those who have monopolised it since 1947. Until then, the cycle remains unbroken – ballots replaced by barracks, law replaced by coercion, and democracy suffocated in the grip of its establishment.

This was the final part of a three part series - you can find the first two parts of the series below.

Part 1

Part 2

Member discussion