The US: A history of regime change

By Aman Abdullah Shahid -

Few features of modern international politics are as enduring - or as controversial - as the United States’ repeated involvement in the internal political affairs of other nations. From covert operations conducted in the shadows of the Cold War to overt military interventions justified under the banners of democracy, human rights, or counter-terrorism, Washington has consistently sought to shape political outcomes beyond its borders. While American policymakers have often framed these actions as necessary for global stability or moral leadership, critics argue that they represent a long-standing pattern of regime change, pursued with little regard for sovereignty or long-term consequences.

The renewed rhetoric coming from the United States, escalated by the capture of Nicolás Maduro - the President of Venezuela - as well as threats against Iran and even Greenland have revived an old debate. Is the United States merely responding to authoritarianism and humanitarian crises, or is it once again deploying a familiar playbook? To answer this question meaningfully, Venezuela must be situated within a broader historical continuum. Regime change, far from being an aberration, has been a recurring instrument of American power for well over a century.

The Roots of Intervention: Early Twentieth-Century Latin America

American involvement in regime change predates the Cold War and is deeply rooted in the geopolitical vision articulated by the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. While ostensibly framed as a warning against European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere, the doctrine gradually evolved into a justification for US dominance over Latin America. By the early twentieth century, this dominance manifested not only economically, but politically and militarily.

The so-called ‘Banana Wars’ provide some of the clearest early examples. Between the 1890s and 1930s, US Marines were repeatedly deployed to countries such as Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Honduras. Governments were overthrown, constitutions rewritten, and financial systems restructured to favour American commercial interests, particularly those of companies like United Fruit. In Nicaragua, the US backed conservative factions and installed pliant leaders while suppressing nationalist resistance movements, most famously that led by Augusto César Sandino.

Haiti offers an especially stark illustration. Following a political crisis in 1915, US forces occupied the country for nearly two decades. During this period, Washington effectively controlled Haitian governance, imposed forced labour policies, and reshaped the state apparatus to serve American strategic priorities. Though the occupation eventually ended, it left behind a fragile political system and entrenched patterns of authoritarian rule.

These early interventions established key precedents - the use of military force to influence leadership, the prioritisation of economic interests, and the belief that US power could legitimately override local political processes. They also set the stage for more sophisticated and covert forms of regime change that would emerge during the Cold War.

The Cold War Playbook: Coups, Covert Operations, and Proxy Power

The Cold War marked the apogee of American regime change activity. Framed as an existential struggle against communism, US policymakers justified intervention across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. Crucially, this era saw the refinement of covert action as a preferred tool, allowing Washington to deny responsibility while shaping outcomes decisively.

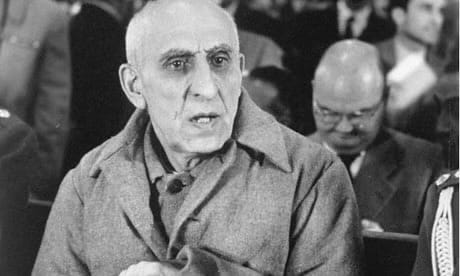

One of the most frequently cited cases is Iran in 1953. When Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh moved to nationalise the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, he provoked the ire of both Britain and the United States. Through a CIA-led operation known as Operation Ajax, Mossadegh was overthrown and replaced with the Shah, whose rule would become increasingly autocratic. While the coup secured Western access to Iranian oil and curtailed perceived Soviet influence, it also sowed the seeds of deep anti-American resentment, culminating in the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

Guatemala followed a year later. In 1954, the CIA orchestrated the overthrow of President Jacobo Árbenz, whose land reform programme threatened the holdings of United Fruit. Though Árbenz was democratically elected, he was portrayed as a communist sympathiser, providing ideological cover for intervention. The aftermath was catastrophic: decades of military rule, civil war, and mass atrocities, particularly against indigenous populations.

Perhaps no region experienced US-backed regime change as intensively as Latin America during this period. In Chile, Washington actively worked to destabilise the socialist government of Salvador Allende, culminating in the 1973 military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet. Declassified documents reveal extensive economic pressure, covert funding of opposition groups, and direct encouragement of military intervention. Pinochet’s subsequent dictatorship, marked by torture, disappearances, and repression, was tolerated - and at times supported - as the price of ideological alignment.

Similar patterns emerged in Brazil (1964), Argentina (1976), and elsewhere, often coordinated through networks such as Operation Condor. In each case, the rhetoric of anti-communism masked a deeper willingness to sacrifice democracy in favour of strategic control.

Southeast Asia and the Costs of Militarised Regime Change

While coups and covert action dominated in some regions, Southeast Asia witnessed a more overt and destructive form of regime change. The Vietnam War stands as the most infamous example. Initially framed as support for a friendly government against communist insurgency, US involvement escalated into a full-scale war aimed at preserving a non-communist regime in South Vietnam.

The human cost was immense. Millions of Vietnamese civilians were killed, entire landscapes were devastated, and neighbouring countries such as Laos and Cambodia were drawn into the conflict. Despite enormous expenditure and loss of life, the effort ultimately failed, with the fall of Saigon in 1975 marking a decisive defeat.

Cambodia illustrates another dimension of unintended consequences. US bombing campaigns destabilised the country, contributing to the rise of the Khmer Rouge. Here, regime change was not directly imposed by Washington, but American actions created the conditions for one of the twentieth century’s worst genocides.

These episodes underscored a recurring flaw in US interventionism - a profound underestimation of local dynamics and a tendency to view complex societies through simplistic ideological lenses.

The Middle East: From Cold War to ‘War on Terror’

The Middle East has been a central theatre of US regime change efforts, driven by a mix of strategic geography, energy interests, and security concerns. Beyond Iran, the region witnessed sustained intervention throughout the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Iraq represents the most consequential example. While the 1991 Gulf War stopped short of overthrowing Saddam Hussein, it set in motion a prolonged campaign of sanctions, no-fly zones, and containment. In 2003, under the pretext of weapons of mass destruction and links to terrorism, the US led an invasion that dismantled the Iraqi state. The absence of post-war planning, combined with the wholesale disbanding of Iraqi institutions, plunged the country into chaos.

The overthrow of Saddam did not yield stability or democracy. Instead, it produced sectarian conflict, empowered militant groups, and destabilised the wider region. The emergence of ISIS can be traced directly to the power vacuum created by regime change.

Libya followed a similar trajectory. In 2011, NATO intervention, led in part by the United States, helped topple Muammar Gaddafi under the guise of protecting civilians. Yet once again, regime change was pursued without a viable political settlement. Libya fractured into competing militias and rival governments, becoming a hub for arms trafficking and human smuggling.

These cases challenge the notion that removing a ruler, however authoritarian, is sufficient to create a functional state. They also expose the limits of military power as a tool for political engineering.

Venezuela: Sanctions, Recognition, and the Modern Regime Change Toolkit

Against this historical backdrop, Venezuela appears less as an anomaly than as a continuation of established practice. Since the rise of Hugo Chávez and the consolidation of the Bolivarian movement, Washington has viewed Caracas as a challenge to US influence in the region. This antagonism intensified under Nicolás Maduro, particularly amid economic collapse and political unrest.

Prior to the capture of Maduro, Venezuela had not yet faced direct military intervention. Instead, the United States employed a combination of economic sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and symbolic actions, most notably the recognition of opposition figure Juan Guaidó as interim president in 2019. This move, coordinated with allies, effectively sought to delegitimise the sitting government and accelerate its collapse.

Sanctions have played a central role. While framed as targeted measures against corruption and human rights abuses, their broader impact on the Venezuelan economy has been severe, exacerbating shortages and humanitarian suffering. Critics argue that such measures constitute collective punishment and function as economic warfare designed to force political change.

The language surrounding Venezuela - references to ‘all options on the table’ and the portrayal of the government as illegitimate - echoes earlier interventions. Before they took action, they built a narrative to justify their actions. What differs in this case compared to previous examples is the increasing reliance on financial leverage, information campaigns, and international institutions. This means although overt force is still on the cards, it is no longer a formality when it comes to regime change.

Patterns, Motives, and Consequences

Across these diverse cases, certain patterns emerge. First, regime change is rarely motivated by altruism alone. Strategic interests - whether ideological, economic, or geopolitical - consistently shape decision-making. Second, the methods evolve, but the underlying assumption remains: that the United States possesses both the right and the capacity to determine political outcomes elsewhere.

Third, the consequences are often long-lasting and destabilising. While some interventions succeed in removing targeted leaders, they frequently leave behind weakened institutions, social fragmentation, and enduring resentment. The gap between stated intentions and actual outcomes is a defining feature of this history.

Conclusion: Venezuela and the Future of American Power

As the war drums are ramped up, the case of Venezuela should not be viewed in isolation. It is part of a long and contested tradition of American intervention, one that spans continents and decades. While the tactics may appear less dramatic than past invasions, the logic remains familiar - pressure, isolation, and the pursuit of political realignment.

As the United States confronts a multipolar world and increasing scepticism toward interventionism, the legacy of regime change looms large. Whether in Venezuela or elsewhere, the lessons of history suggest that imposed solutions rarely produce the stability or democracy they promise. Understanding this record is essential, not only for assessing current policy, but for imagining alternatives that respect sovereignty, prioritise diplomacy, and acknowledge the limits of power.

Member discussion