We do not Have to Celebrate Criminals to Preserve History

By Wali Khan -

In June 2020, the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol was toppled by protestors and discarded in the city harbour. Colston was a 17th century merchant, who had long been celebrated in Bristol for his philanthropy. His charitable donations to schools, churches and almshouses earned him a statue in the city. However, a significant part of his legacy had often been overlooked: Colston was a senior figure in the Royal African Company, which was responsible for transporting 80,000 enslaved Africans - many of whom died during the brutal journey across the Atlantic.

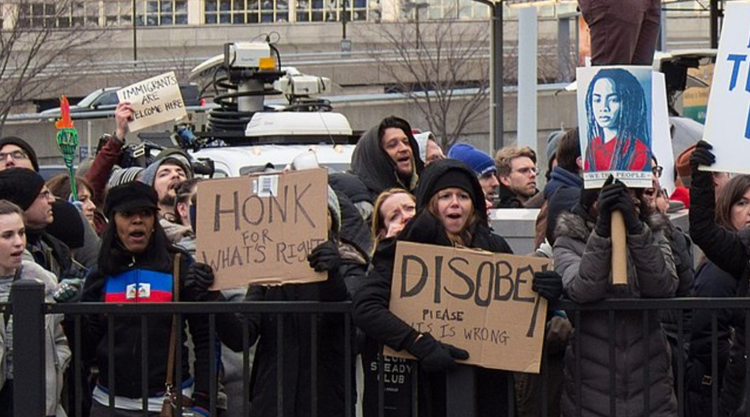

Many deemed the protestors actions disgraceful, including government officials like Priti Patel. Naturally, civil disobedience has never been popular with those in power. For that very reason, the public must be civilly disobedient when the government does not consider valid concerns important. It is one of the most effective tools of societal progression, often the precursor to revolutionary change as seen in cases such as the civil rights movement and Mahatma Gandhi’s activism for the emancipation of the sub-continent. Crucially, it must be rooted in civility. Thus protests must employ non-violent measures of resistance.

Ideally, civil disobedience would be unnecessary, and our systems would be able to implement the right policies and act in accordance with justice through their own volition. However, in many instances, this is not the case. The statue of Edward Colston was subject to numerous lawful attempts of removal, but these were ignored. One petition, organised by the online campaigning group 38 degrees, gained over 11,000 signatures, yet it still failed to convince the authorities.

Fortunately, once the statue was toppled, councils across the country acknowledged the importance of removing such figures from public life. Nearly 70 tributes to individuals with similar histories to Colston were removed by authorities in the UK. Again, ideally, this type of action would never be necessary; however the case of Colston highlights how civil disobedience can be an important catalyst for change and progress.

Furthermore, the protestors who toppled the statue, the “Colston Four”, were all acquitted, meaning they faced no legal punishment. It was argued that they acted in self-defence because the statue itself was oppressive and its presence was a symbol of racial injustice. Their acquittal signals the power of just civil disobedience in progressive democracies. In a country like the United Kingdom in 2025, the consequences of opposing injustice in a civill manner are not extreme.

Therefore, to not be civilly disobedient in the face of injustice would be to allow injustice to perpetuate, resulting in a much greater societal harm than peacefully breaking a law to advocate for what is right.

The British Prime Minister at the time, Boris Johnson, claimed that removing statues is “to lie about our history.” This statement is disingenuous on numerous counts. Firstly, a public statue or tribute is not simply a historical monument; it is a celebration of an individual. For example, nobody would have implored Germany to maintain Nazi monuments in public for the sake of history. This is a lazy attempt to excuse the actions of villains of the past. For many, their sense of nationalism, of what they believe made Britain “great”, is more important than the lives that were destroyed along the way. We must not allow this to be the case. Britain is great because it has been able to overcome its problematic, brutal past to become a diverse, democratic nation. To ignore the crimes of our past is to erase history. To present Edward Colston as a hero is to lie about our history.

Maintaining these truths is important, we must learn from our past mistakes in order to avoid making them again. Thus, I believe these statues or tributes should not be destroyed or completely erased from society in any manner. They should be placed in museums or similar institutions where we are able to provide context for their presence. In these environments, we can teach people about the good and the bad rather than hoisting problematic individuals on top of our buildings to look down on the descendants of those they oppressed.

As for those who claim that these individuals deserve statues because of the good they did for their communities:

You go to school, and after your teachers, you thank the man who funded it. You go to church, and after God, you thank the man who paid for the pews. You visit the hospital, and after the doctor, you thank the man who made it possible. You rest your head in the almshouse, and after the staff, you thank the man who gave you a roof. All of it - your education, your prayers, your healing, your shelter - paid for by the same man. So you celebrate him. You name your schools after him. Your churches. Your streets. You build him a statue. And centuries later, long after he is gone, and we are gone, your grandchildren’s grandchildren walk past that statue and remember how great a man he was.

But with every book you read, every prayer you said, every cure you received, and every night spent in that almshouse, you forgot who truly paid the price. Not the man who funded it, but the 80,000 souls enslaved and trafficked by the Royal African Company he helped lead.

Sons stolen in the night, never seen again by their mothers. Daughters kidnapped, abused, and sold. An endless cycle of pain, humiliation, and torment - all so he could afford to be remembered.

Yes, Edward Colston gave you comfort. Yes, he gave you charity. But only after stealing their lives. The almshouse walls may have kept out the wind, but they also blocked out the screams. Screams of those who paid for your stay with their suffering.

Now his statue towers above the city, just as he once towered over the people he helped enslave. Praised and glorified for the good he did, paid for by the blood of others.

Member discussion